AP Syllabus focus:

‘Students view the area under a curve above the x-axis on [a,b] as a definite integral, interpreting the integral as accumulation of rectangular strip areas.’

Understanding the area under a single curve helps students connect geometric ideas with integration, showing how definite integrals measure accumulated quantities by summing infinitely thin rectangular slices.

Area Under a Single Curve

When studying the area beneath a smooth curve, AP Calculus AB emphasizes viewing a definite integral as an accumulation of many extremely thin slices. This perspective aligns integration with geometric reasoning and lays essential groundwork for more advanced applications of integrals.

Interpreting the Region Under a Curve

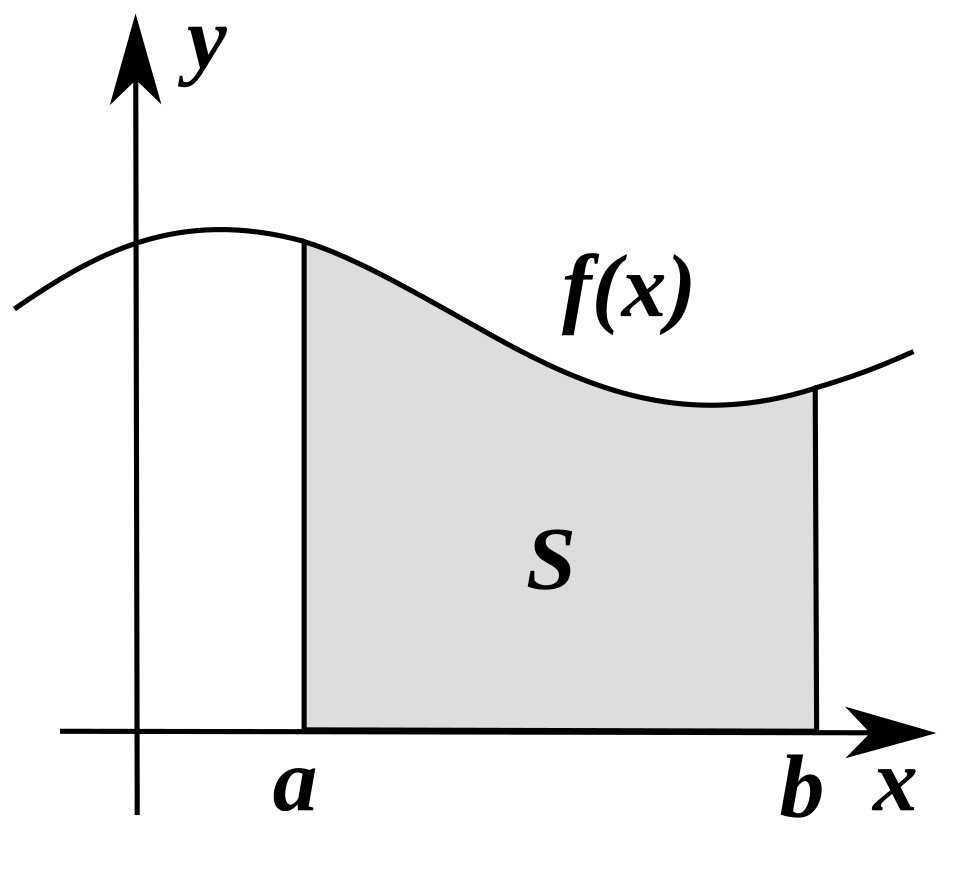

Consider a continuous function defined on a closed interval . The region whose area we want to measure lies between the graph of the function, the x-axis, and the vertical lines at and . AP Calculus AB requires students to think of this bounded region as being composed of many narrow vertical strips. Each strip represents a tiny rectangular approximation whose width is extremely small and whose height corresponds to the function’s output at a specific x-value.

A graph of a function above the x-axis with the region between and shaded and labeled by . This diagram highlights the interpretation of the definite integral as the geometric area under a single curve. The visualization emphasizes how the integral measures accumulated area across the interval. Source.

This viewpoint directly connects geometric intuition with algebraic accumulation. As the widths of these rectangular strips shrink, the total combined area of all strips approaches the exact area under the curve. The definite integral is defined precisely as this limiting value.

Viewing Area as Accumulated Change

The central idea of the syllabus statement is that the definite integral represents “accumulation of rectangular strip areas.” To understand this, students imagine the area as the total contribution from infinitely many slices. Each slice adds a small amount to the total, and the integral gathers—or accumulates—these contributions.

This interpretation reinforces the broader conceptual view of integrals as accumulators of change, not just tools for computing geometric area. While the focus here is geometric, the underlying structure mirrors the way integrals will later represent quantities such as displacement, growth, or net change.

The Definite Integral as Area

To formalize the idea of accumulation, the definite integral expresses how these curved regions can be measured exactly. When is continuous and on , the definite integral from to gives the exact geometric area between the curve and the axis.

= Height of each vertical strip (units depend on context)

= Input variable determining location of each strip

= Interval endpoints defining the region of accumulation

A normal sentence must come here to maintain required spacing before any other formal block. This mathematical structure encapsulates the limit of accumulated rectangular areas as their widths approach zero.

How the Definite Integral Represents Accumulation

The definite integral uses a limit process that transforms approximate sums into an exact quantity. This requires imagining:

Many narrow rectangles whose heights equal the function value at selected input points.

A very small width, often called , representing how thin each rectangle becomes.

A sum of all rectangular areas, expressed as for each strip.

A limit as , meaning infinitely many slices are included with no width.

Through this lens, the integral operates as a perfect sum—an accumulation without approximation error.

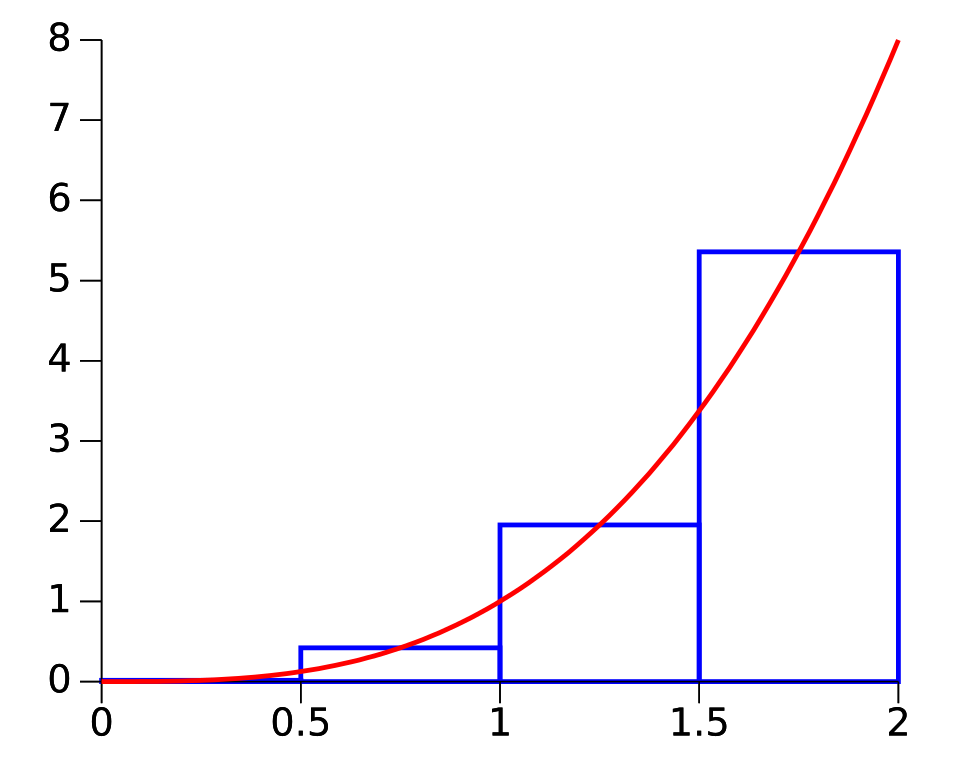

A graph of with four midpoint-based rectangles approximating the area under the curve. Each blue rectangle illustrates how at the midpoint of each subinterval forms an approximation to the definite integral. This visualization demonstrates how Riemann sums refine toward the exact value . Source.

Conditions for Area Interpretation

For AP Calculus AB, the interpretation of the definite integral as area applies specifically when:

The function is continuous on the entire interval. Continuity ensures that the height of each rectangular strip behaves predictably.

The function is nonnegative on . Area must be nonnegative, so interpreting the integral purely as area requires the curve to lie on or above the x-axis.

The interval is closed and finite, guaranteeing that the region being measured is well-defined.

If dips below the x-axis, the integral still measures accumulation, but no longer corresponds directly to geometric area. Instead, such integrals are covered in other parts of the course as net signed area, not the focus of this subsubtopic.

Connecting Visual and Analytical Perspectives

To fully grasp area under a curve, students integrate both graphical and algebraic perspectives:

Graphs illustrate how the region appears and help confirm the function stays above the axis.

The algebraic representation using a definite integral expresses the same area numerically.

The conceptual model of accumulating tiny slices bridges the two viewpoints.

This synergy reinforces why definite integrals are the main analytic tool for quantifying areas bounded by curves.

Summary of Key Study Points

The area under a nonnegative, continuous function over is represented by a definite integral.

The integral reflects accumulation of many thin rectangular strips whose heights are determined by the function.

This geometric interpretation is foundational for understanding integrals as measures of accumulated quantities.

FAQ

The rectangular strips arise from partitioning the interval into smaller and smaller pieces, with each strip representing an approximation to a portion of the area.

As the width of each strip shrinks, the total combined area of all strips approaches a single exact value.

The definite integral formalises this process by taking the limit of these sums, ensuring the area under the curve is captured precisely rather than approximately.

Area must be non-negative, so the interpretation only applies when the function values are non-negative. When the graph lies below the axis, the definite integral measures signed accumulation instead.

This means the output of the integral would represent net value rather than geometric area, preventing a pure area interpretation.

Clear indications that help include:

• A smooth curve without oscillations

• Clearly marked interval endpoints

• A distinct region between the curve and the x-axis

• An axis scale that allows approximate comparisons of height

These features help you estimate area qualitatively even before calculating a definite integral.

Continuity ensures there are no jumps or gaps in the curve. This means the height of each infinitesimal strip changes smoothly across the interval.

Because the curve behaves predictably, the summation of infinitely many strips captures the full region accurately. Discontinuities could create undefined behaviour or missing area segments.

Yes. Many distinct functions can enclose the same area on the same interval.

For example, a tall narrow curve and a short wide curve may balance out to the same accumulated area.

Area depends on total accumulation rather than the specific shape of the curve, as long as the integral of the function over the interval matches the same overall value.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function f is continuous and non-negative on the interval [2, 5]. The area under the curve y = f(x) above the x-axis from x = 2 to x = 5 is represented by the definite integral ∫₂⁵ f(x) dx.

Explain, in terms of accumulation, what this integral represents.

Question 1

Maximum 3 marks.

• 1 mark: States that the integral represents the total accumulated area under the curve from x = 2 to x = 5.

• 1 mark: Mentions that this area is found by summing infinitely many thin rectangular strips.

• 1 mark: Explains that the integral gives the exact limit of these accumulated strip areas as their width approaches zero.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Consider the continuous function g defined on the interval [0, 4]. The graph of y = g(x) lies entirely above the x-axis.

You are told that g increases steadily over the interval, and its values at key points are:

g(0) = 3

g(2) = 5

g(4) = 8

(a) Explain why the area under the graph of g from x = 0 to x = 4 can be interpreted as a definite integral.

(b) Using the information above, give a justified estimate of the area under g on [0, 4] by dividing the interval into two equal subintervals.

(c) Explain whether your estimate is likely to be an underestimate or an overestimate, and why.

Question 2

Maximum 6 marks.

(a) (2 marks)

• 1 mark: States that because g is continuous on [0, 4], a definite integral can represent the area under the curve.

• 1 mark: Notes that the graph lies above the x-axis, so the integral corresponds directly to geometric area.

(b) (2 marks)

• 1 mark: Divides the interval into [0, 2] and [2, 4], using g(0) and g(2) for one rectangle and g(2) and g(4) for the other, or equivalent reasoning.

• 1 mark: Produces a reasonable estimate, for example using the midpoint or trapezium rule.

(For trapezium rule: area estimate = 1/2 × (g(0) + g(2)) × 2 + 1/2 × (g(2) + g(4)) × 2 = 2 × (g(0) + 2g(2) + g(4)) / 2 = 2 × (3 + 10 + 8) / 2 = 21.)

(c) (2 marks)

• 1 mark: Correctly identifies that the estimate is likely an underestimate because g is increasing.

• 1 mark: Explains that using left-hand or trapezium estimates on an increasing function typically gives an area smaller than the true area, as the rectangles or trapezia lie below the curve.